In attempting to understand psychiatric symptoms and physical illness, especially those conditions traditionally labeled “psychosomatic,” medicine often confronts a problem of language. Neurobiology is complex, subjective experience is difficult to quantify, and patients frequently feel misunderstood when their suffering is reduced to diagnostic codes or neurotransmitter diagrams. Metaphor, when used carefully, can serve as a powerful educational bridge. One such metaphor is to imagine the human mind–body system as an electrical network: psychiatric symptoms as a short fuse, psychosomatic illness as burnt wiring after an electrical surge, and psychotropic medications as surge protectors. Though imperfect, this framework offers a coherent way to explain distress, breakdown, and treatment without moral judgment.

⸻

The Nervous System as an Electrical Network

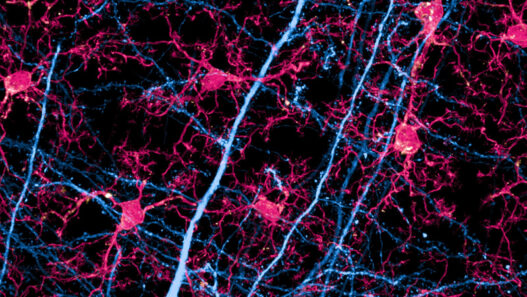

The brain and nervous system already lend themselves to electrical imagery. Neurons communicate through electrochemical signals; action potentials fire, circuits strengthen or weaken, and networks synchronize or fragment. In this sense, human functioning resembles a power grid designed to handle fluctuating demands. Stress, trauma, genetic vulnerability, and environmental pressures all increase “load” on this system. When regulation is intact, the system adapts. When regulation fails, symptoms emerge.

The metaphor is not meant to suggest that humans are machines, but that systems—biological or engineered—share common principles: thresholds, feedback loops, and failure points.

⸻

Psychiatric Symptoms as a Short Fuse

A short fuse exists to prevent catastrophic damage. When electrical current exceeds safe limits, the fuse breaks the circuit, cutting off power. In psychiatric terms, symptoms such as panic attacks, emotional dysregulation, intrusive thoughts, dissociation, or psychosis can be viewed not simply as malfunctions, but as emergency shutdowns.

Anxiety, for example, may represent a nervous system that detects threat too quickly and trips the fuse before reflective thought can intervene. Depression can be understood as a conservation mode—power reduction after prolonged overload. Mania may be the opposite: an uncontrolled surge that bypasses the fuse entirely. In this framing, psychiatric symptoms are not moral failures or signs of weakness; they are protective responses that have become maladaptive.

Importantly, a short fuse does not mean the appliance is “bad.” It means the system is overwhelmed. Replacing the fuse without addressing the underlying overload may restore function temporarily, but the risk remains.

⸻

Psychosomatic Illness as Burnt Wiring

If a short fuse fails—or if overload is chronic—the damage moves deeper into the system. Psychosomatic illness can be likened to wiring that has been burnt out by repeated surges. Chronic stress, unresolved trauma, and prolonged emotional suppression do not simply disappear; they are absorbed by the body.

Conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pain syndromes, fibromyalgia, tension headaches, and certain autoimmune flares often sit at the intersection of mind and body. In the electrical metaphor, the current has passed beyond the fuse and damaged the infrastructure itself. The result is not imaginary pain, but altered signaling, inflammation, and dysregulated physiology.

This framing challenges the false dichotomy between “real” physical illness and “psychological” illness. Burnt wires are real. They require repair, not dismissal. Telling a patient their illness is “all in their head” is equivalent to telling someone with damaged wiring that the blackout is imaginary.

⸻

Psychotropic Medications as Surge Protectors

Psychotropic medications can be conceptualized as surge protectors rather than cures. A surge protector does not fix damaged wiring, nor does it eliminate fluctuations in current. Its role is to absorb excess energy, smooth spikes, and prevent further damage.

Antidepressants, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics modulate neurotransmission, dampening extremes and widening the margin of safety. They reduce the likelihood that the fuse will blow or that additional wiring will burn. In doing so, they create a stable window in which repair can occur.

This metaphor helps counter two common misconceptions: that medications “fix everything,” and that they merely “mask symptoms.” Surge protectors are neither magic nor deceptive; they are protective devices. Without them, the system may remain too unstable for meaningful psychological, behavioral, or social interventions to take hold.

⸻

Repair Requires More Than Protection

No electrician would install a surge protector and ignore damaged wiring. Likewise, long-term healing in psychiatry often requires psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, social support, and meaning-making. Therapy can be understood as rewiring—creating new circuits, strengthening regulation, and redistributing load. Practices such as mindfulness, exercise, sleep regulation, and relational safety reduce overall current demand on the system.

In some cases, medication may be temporary; in others, it may be a long-term component of maintaining stability. Neither choice implies failure. Some systems are built with inherent vulnerabilities and require ongoing protection to function safely.

⸻

Educational and Ethical Implications

This metaphor has educational value because it reduces stigma. Patients are not “broken”; their systems have been stressed. Symptoms are not betrayals; they are signals. Medication is not a crutch; it is a safety device. Clinicians, in turn, are not merely suppressing symptoms but preventing further damage while facilitating repair.

Ethically, the metaphor reinforces humility. Electrical systems fail in predictable ways under stress; human systems are no different. Understanding this shifts psychiatry away from blame and toward care.

⸻

Conclusion

Viewing psychiatric symptoms as short fuses, psychosomatic illnesses as burnt wiring, and psychotropic medications as surge protectors offers a compassionate and integrative model for understanding mental and physical suffering. It acknowledges the reality of symptoms, respects the body’s protective intelligence, and situates medication within a broader framework of healing. While no metaphor can fully capture the complexity of the human mind, this one reminds us of a fundamental truth: systems under strain do not need judgment—they need protection, repair, and understanding.